Soaring energy prices will push up broader inflation across Europe this year, hurting consumers and threatening the region’s post-pandemic economic recovery, economists are warning.

Benchmark European gas prices have already tripled this year, even before peak winter demand kicks in. Norway’s Equinor, one of Europe’s biggest gas suppliers, said last week that high energy prices could last well into 2022 and warned of possible price spikes.

“Brace for a surge in eurozone gas inflation,” said Claus Vistesen, chief eurozone economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics. Rising energy prices will drive “an acceleration in the eurozone’s headline inflation,” added Daniel Kral, economist at Oxford Economics.

There are multiple reasons behind the price surge, from low European energy stocks and US storms that curbed Texas gas exports, to rebounding demand as economies reopen. Climate change policies that seek to incorporate the rising price of carbon have also had an effect.

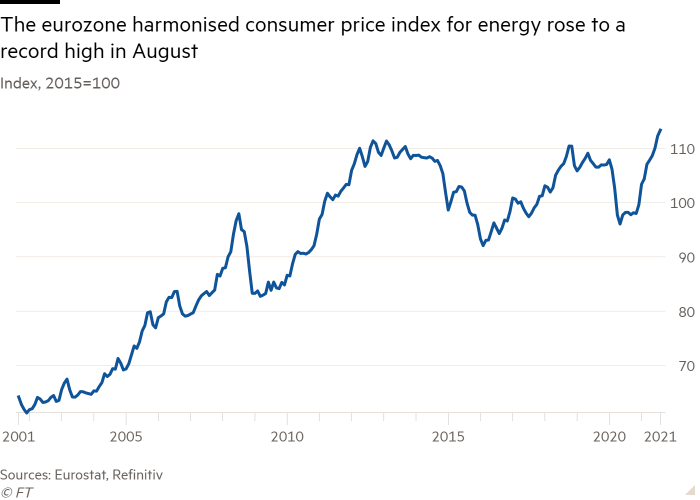

The eurozone’s consumer price index for energy has already risen to its highest level since records began in 1996. In August, its 15.4 annual per cent increase, the series’ biggest jump since the global financial crisis, pushed the eurozone’s headline inflation rate to a decade high of 3 per cent.

That is well above the European Central Bank’s 2 per cent inflation target. But ECB officials and economists have said they expect the rise to be temporary, because of one-off factors such as supply chain disruptions, as the developed world emerges from the pandemic.

Even so, a prolonged rise in energy prices could derail those inflation forecasts. Higher energy bills would also hit household budgets and consumer confidence, threatening economic recovery.

It “would act as an effective tax increase on households . . . reducing their discretionary outlays and slowing Europe’s recovery, which has largely been driven by the rebound in consumer spending,” said Nick Andrews, analyst at Gavekal, an investment research group.

Energy accounts for almost 10 per cent of consumer spending in Europe, so “the double-digit yearly increase of energy prices . . . is having an important effect,” said Peter Vanden Houte, ING’s chief economist.

The impact of higher energy prices goes beyond the EU. In August, the annual rate of energy price inflation rose by more than 60 per cent in Norway, topped 20 per cent in Canada and the US, and registered double-digit increases in South Korea, Chile and Mexico.

It has had ripple effects on other commodities, pushing up the price of oil and potentially food. It has also prompted governments to react.

Last week, Spain announced a €3bn raid on energy companies’ profits. Italy’s government has already spent about €1.2bn to subsidise consumer bills. Some EU lawmakers have also called for an investigation into whether Russian gas exporter Gazprom manipulated gas prices.

Alexei Miller, head of Gazprom, said on Friday that low stocks could force European gas prices to new highs through the winter, according to state-run Tass newswire.

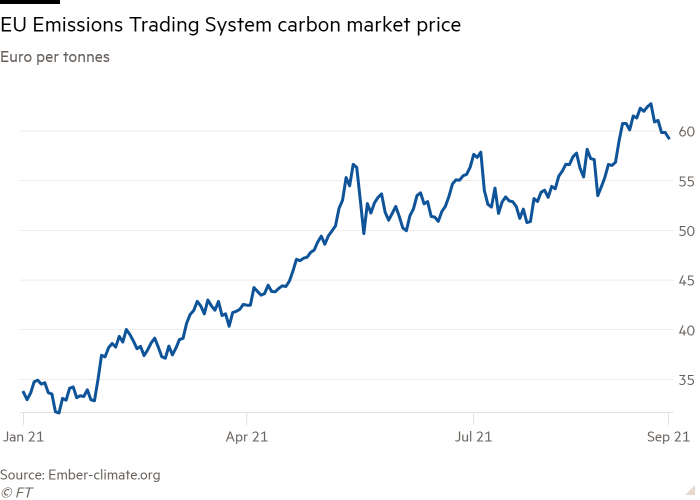

On top of that the price of carbon permits, a central plank in EU plans to slash emissions, has almost doubled this year. This “suggests that energy bills will be higher in the future,” Jessica Hinds, economist at Capital Economics, said.

The immediate inflationary impact of higher energy prices is all but unarguable. Barclays economist Silvia Ardagna estimated it could push up headline eurozone inflation to a peak of 4.3 per cent this November.

Whether that will lead to higher core inflation — a measure which strips out volatile energy and food prices and which the ECB watches when gauging whether to change monetary policy — is another matter.

“Higher energy inflation alone won’t push the ECB,” Vistesen said.

Nor will higher energy prices necessarily lead to slower overall growth because high household savings accumulated during lockdown could leave consumer spending power largely unaffected.

The recovery in employment, as reflected in high job vacancies, could also help. “We are not making any change to our growth outlook at this time,” Ardagna said.

Still, high energy costs will with little doubt be a problem for many, whether those are less well-off individuals or companies for which energy is an important input.

“A cold snap at the start of winter is now a real economic threat, for low income households and some manufacturing sectors,” Vistesen said.

Additional reporting by Max Seddon in Moscow

Energy prices will push up inflation across Europe, economists warn - Financial Times

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment