The Biden administration has explicitly linked its foreign policy agenda to the goal of improving the economic circumstances of the United States, especially the middle class. It seems natural that a country would connect its prosperity to how it navigates the often-treacherous waters of international relations. But are these goals — national wealth and security — easily pursued together?

There are at least five big issues to consider when assessing the goal of linking America’s economic well-being to its national security policies. First, while there are similarities and connections, a state’s national security goals often pull in different directions than its foreign economic ambitions, which themselves can be at odds with its domestic economic priorities. Where are the tensions between economics and national security, and can a thoughtful grand strategy overcome them? Second, it is important to comprehend how the American economy functions — both in the past and the present — and to better understand what role federal policy has played in its development. Third, what goals and values have animated U.S. economic statecraft in the past? The United States has, throughout its history, viewed the dangers and opportunities of the international economy differently than other states. Fourth, after pursuing a largely hands-off approach to the global economic order from its founding through the 1930s, the United States reversed course after World War II to pursue an ambitious foreign economic policy. This economic statecraft was consequential if at times inconsistent and erratic. Finally, the United States and the world are entering a new period of economic transformation that will generate difficult dilemmas and questions. How these dilemmas and questions are confronted will shape how successful the administration is in incorporating economics into its national security strategy, as well as shape the next decades for both the United States and the world.

Tension Between Economics and Security

Writ large, any national grand strategy should seek both prosperity and security, and there are many reasons to believe these goals are interconnected. Historically, however, there are at least four major tensions between foreign economic and national security policy.

First is a chicken and egg story — which comes first, wealth or security? It is difficult to generate productive economic activity in an unstable, insecure environment. A national security policy that removes threats and dangers and provides stability creates a far better environment for economic growth. On the other hand, providing security is costly. Subsidizing standing militaries and bureaucracies that support them is not only expensive, but it also involves opportunity costs by removing otherwise productive citizens and organizations from contributing to the economy. Spending too much wealth on security (i.e., the military) can decrease a nation’s productivity and lead to economic decline. Privileging the economy over security, on the other hand, can lead to a state having less influence on the world order in which it operates. More worryingly, it can expose a state to coercion, predation, and even conquest. History provides stark examples of the danger of both spending too much and too little on security.

The second dilemma is related and somewhat contradictory. While eliminating destabilizing violence and lawlessness is necessary for economic growth, the greatest periods of technological, governmental, financial, and even sociocultural innovation have often coincided with intense geopolitical competition and even war. Western Europe’s rise to economic dominance from the 17th through the middle of the 20th century can, in part, be attributed to a fierce security competition on the continent, where to fall behind was to risk second-rate status or even extinction. European imperialism was driven by similar pressures and propelled by the innovations produced by continental competition (modern banking and finance, efficient governance, steam, rail, telegraph, advanced medicine, etc.). These in turn fostered similar reforms globally among nationalizing and decolonizing movements trying to escape the grip of European imperial power. It is no accident that the period that witnessed the greatest geopolitical upheaval also witnessed world historical economic growth and unprecedented increases in life expectancy. The foundations of the computing and telecommunications revolution, to give the most recent example of security-driven innovation, had its roots in the Cold War competition.

Third, different theories and mechanisms drive the effort to acquire greater wealth as opposed to obtaining greater security. Success in economics is measured by absolute gain. Economic productivity and wealth creation is driven by the laws of comparative advantage, where exchange between individuals, communities, and nations is mutually beneficial. Security, on the other hand, is measured by relative power. In other words, it matters less how much a state’s power increases in absolute terms than how its position changes compared to its competitors. This generates a conundrum for grand strategy — should a state pursue global economic exchange that will increase its wealth if it also enriches, perhaps more, a potential adversary? This dilemma has been at the heart of U.S. policy toward China over the past 30 years.

The fourth tension involves interdependence. Increased trade, commerce, and financial interactions between nations makes them more connected and in some sense dependent upon each other. Some argue this interdependence increases security, as nations develop a common interest in maintaining the mutual gain that comes from their shared, interwoven economic activity. Political scientists often refer to the capitalist peace. Others — who often self-identify as realists — worry this is an illusion. Ultimately, a state’s desire for security and power will always trump its desire for wealth and economic gain, and no level of interdependence will prevent it from pursuing its interests, even if those interests threaten a conflict that would undo the economic system and interdependence. Others even go so far as to suggest that interdependence dangerously increases a nation’s security vulnerability and may even heighten friction between states.

Despite vigorous debate among international relations theorists, economists, and historians, there is no agreed upon resolution to these dilemmas between national security and economics. The best grand strategies are the ones that most effectively recognize and reconcile these tensions between security and economics. The United States has also long had a different way of viewing and resolving these tensions than other powers.

America’s Economic History

How should we understand the American economy — its history, current state, and future path? How is wealth generated and distributed, and how do these practices and outcomes compare to other states? Understanding how the U.S. economy works, and the role of national policy in its development, is critical to incorporating it into a national security strategy.

The United States has long been a wealthy nation, even before its political founding. It became the world’s largest economy in the late 19th century, but not merely because of its size. It also had the largest per capita gross domestic product. Despite profound changes in the global economy, and the fact that the second-largest economy has changed often (Great Britain, Germany, the Soviet Union, Japan, now China), the United States has maintained its leading position for over 130 years. Its recent percentage of global GDP is not considerably different than it was in 1913.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States excelled at the activities that generated wealth in the modern world: agricultural production and resource extraction; manufacturing and industrial output, first based on crafts and small manufacturing before transitioning to mass production; effectively overcoming geographical barriers to transport goods across land and sea; excellence in the fields that facilitated trade, both within the United States and globally, including banking and finance, insurance, accounting, and law; and communicating over longer distances and at increasing volume and speed.

America’s impressive and sustained economic success has been based on a number of factors. It possesses enormous amounts of fertile land and diverse natural resources, as well as navigable rivers, excellent access to two oceans and a gulf, with good ports. It has long emphasized early education and historically had high levels of literacy and numeracy. America’s legal system prioritizes the protection of private property, both physical and intellectual. Relatively open and large-scale immigration injected youth and creativity into the population at key moments. American politics and culture incentivize entrepreneurship and small business creation. World leading research organizations, especially American universities, have consistently generated inventions, innovation, and adaptation. This history is deeply stained, of course, by a multitude of sins, the worst being the horrific legacy of slavery and persistent racism toward black Americans. Compared to its competitors, the United States has demonstrated an ability and at times a willingness to acknowledge and work to correct these pathologies, if too slowly and far from completely.

What role has national policy played in America’s economic well-being? Over its history, the federal government has had six primary responsibilities regarding the economy. The first is national tax and budgetary policy, including debt management, which is largely shaped by the Congress in cooperation with the executive branch. The second is monetary policy. Both were transformed in 1913, when the United States inaugurated a peacetime income tax and created the Federal Reserve banking system. The third is land policy — how would the United States distribute and regulate its vast territory? Fourth is regulatory, competition, and antitrust policy, another largely 20th century innovation that the progressives initiated and more fully emerged during President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. The fifth, social welfare, insurance, and health provision, also emerged from the New Deal but expanded significantly under President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs, supplemented by health care expansion under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama. The sixth — and the only one that deals explicitly with international economics — is tariff and trade policy. Despite the global component, however, tariffs and trade were seen until the 20th century as the primary source of federal revenue and a way to protect nascent American manufacturing, agriculture, and industry.

These six roles seem impressive. The U.S. national government, however, has always done less in each of these categories and in overall management of the economy than other advanced countries. On many aspects of domestic life affecting most Americans, ranging from education to criminal justice to transportation, local and state governments matter more. Even regulatory and social transformations ushered in by the New Deal and Great Society reflected far less intervention than, say, the actions taken by national governments in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Japan, or China.

In addition, most U.S. economic policy is overwhelmingly focused on the domestic economy, and its percentage of gross domestic product that comes from trade is lower than others. Unlike most other nations, whose monetary policy is as much concerned with the external value of its currency, the United States rarely worried about formal exchange rate policy. While the American economy is obviously influenced by the global economy, and the economy of the rest of the world has long been affected by the United States, foreign economic policy plays a less prominent role than it does in many other countries.

The United States Is Different

The relatively small role of the federal government, at least compared to other states, and its focus on its domestic economy highlight a few of the ways the United States views the relationship between economics and national security that are somewhat different from other powers, both in the past and today.

Historically, the United States has an attitude toward the international economic activity that can be puzzling to other countries. For example, the United States has throughout its history been less dependent on trade than most other powers. It possesses a massive domestic market, which it has focused on developing. Much of its trade is with its neighbors Mexico and Canada. And contrary to conventional wisdom, it has never been a free trade country. It has always employed tariffs, often quite high, both to generate government revenues (in the 19th century) and protect and nurture nascent domestic industries.

On the other hand, while it has not been a free trade country, it has always passionately believed in the freedom to trade. For the United States, trade has always been about more than economic gain. The founders believed that commerce, between peoples and nations, was the best way to guarantee peace between states. When this freedom to trade was threatened, the United States became apoplectic: The War of 1812 and the U.S. intervention in World War I were arguably driven in large measure by outrage over interference with American freedom to trade with whomever it wanted. The United States has sometimes taken the complete opposite track when the freedom to trade is threatened, seeking to isolate itself from global commerce. Thomas Jefferson’s Embargo Acts and much of U.S. foreign economic policy during the 1930s (and to a lesser extent, the 1970s) reflected this instinct. War, on the one hand, and self-isolation, on the other, while wildly different responses, were two sides of the same coin. America does not believe anyone should curtail its freedom to engage the world through the peace-inducing qualities of mutually beneficial commerce. Arguably, these responses had less to do with geopolitics (each was potentially foolish), or even wealth, given the relatively small exposure the U.S. economy had to trade. Rather, they emanated from a broad set of principles and frames for how the United States understood the world.

This helps explain the significance of the much derided “open door” policy of the United States. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the European powers exploited a China rocked by deep political turmoil to carve out separate economic spheres for themselves. U.S. Secretary of State John Hay tried to establish the principle that no state should have exclusive trading rights in any part of China and all states should be allowed to compete freely for its trade. While the open-door notes were specific to China, and the United States offered mere words and no force to back its declaration, the notes reflected principles held by the United States before and after this particular episode. It was less about economic gain — trade with China played a negligible role in the overall American economy — than the idea that a world where sovereign states were allowed to trade freely was one that would be more peaceful. This highlights another key part of America’s philosophy toward economics and security — its profound disapproval of formal empire, which it associated with dangerous European behavior.

Academics have argued endlessly about America’s historical attitude toward empire. It is correctly pointed out that America’s relentless drive to establish continental hegemony in North America over native populations was perhaps the most extreme form of imperialism. The United States also acquired island territories in the Caribbean and Pacific. It fought a brutal counter-insurgency in the Philippines, while allowing itself to routinely intervene in the domestic affairs of its Latin American neighbors. If imperialism is defined in the broadest possible way — to include cultural influence and economic sway — the United States rivals any historical hegemon.

Unlike the European empires, however, the United States sensed from its founding that the process of acquiring, subduing, and exploiting overseas colonies for economic gain was politically corrupting, both by poisoning domestic institutions and making international affairs more prone to war. The political logic was simple but profound: Formal empire exploits people unjustly and can be maintained only through coercion. Coercion requires expensive standing militaries and large, intrusive bureaucracies, which demand high taxation; highly regulated, often mercantilist economies; and powerful, often non-representative central governments. And the more militarized the world, the greater temptation to resort to force. In a world without empire and formal colonies, however, large militaries, higher taxation, and overweening central governments are less needed. Citizens can pursue gain and mutual benefit through commerce, which leads to peace among nations. There is no doubt this stylized understanding of world politics contained within it contradictions and elements of hypocrisy. To an extent rarely recognized, however, the United States associated European empire with tyranny and war, and saw free commerce as a way to avoid those evils.

American Foreign Economic Policy After 1945

The United States abandoned its hands-off relationship with the international economy as a result of World War II. A variety of considerations motivated this shift, including its own economic fears. Contrary to critical accounts, however, economic order building was inspired less by a desire to create an American empire, formal or informal, than to break what it saw as the links between empire, autarky, and war. A world with stable, mutually beneficial trade was more likely to be prosperous and peaceful. These goals motivated a variety of initiatives, ranging from the institutions and rules that emerged from the 1944 Bretton Woods conference to the Marshall Plan.

It is important to remember that the history of America’s foreign economic policy and American national security policies since 1945 followed distinct paths and histories, sometimes overlapping, sometimes at odds, other times discrete and unconnected. In other words, the history of America’s role in this global economic order is not the same as the history of the Cold War competition with the Soviet Union. Furthermore, there was not, as is often thought, a single liberal world economic order that emerged in 1945 and persists today. Instead, postwar American foreign economic policy can be divided into at least four different periods.

The first period, the Bretton Woods era, lasted from the immediate postwar years to the early 1970s. This period was not, as often thought, animated by a desire to increase globalization, open economies, and foster interdependence. Instead, the aim was to take the best elements of the free enterprise system while avoiding its worst elements. It was believed that the interwar period revealed the dangers of unregulated globalization: international debt and massive swings in investment and capital flows leading to currency volatility, which in turn created pressures for economic nationalism, trade blocs, and beggar-thy-neighbor economic policies. These in turn encouraged autarky on one hand and imperial preferences on the other, generating (at least in the minds of American statesmen) the seeds of authoritarianism, war, and conquest. The statesmen who met at Bretton Woods in 1944 sought above all else to stabilize currencies, even at the expense of free trade and capital movements, and prioritized domestic economic priorities and national reconstruction, as well as regional integration, over globalization and free trade.

The Bretton Woods system successfully achieved its goals — a postwar depression was avoided and Western Europe and Japan recovered and grew rapidly. The system possessed the seeds of its own dissolution, however. Fixed exchange rates are difficult to maintain for long periods. Diverging rates of inflation between countries change the real value of the currency, unless there is a mechanism to readjust those values. Before World War II, the movement of gold to cover balance of payments deficits was supposed to do the trick. Since national monetary supplies were based on gold, losing the metal to cover deficits required raising interest rates and deflating the domestic economy to return it to balance of payments equilibrium. The link between gold, the balance of payments, and the domestic economy was largely broken in the postwar period. No national government, least of all that of the United States, would deflate its economy and increase unemployment to balance its international payments. The United States refused to undertake either the domestic or international policies that would have been needed to maintain the fixed exchange rate regime, which began unraveling in the 1960s before collapsing in the early 1970s.

The second postwar period of U.S. foreign economic policy was the early 1970s through the early 1990s, which might be thought of as the most volatile, disruptive period of globalization. Efforts to reconstitute the fixed exchange rates failed and international capital flows ballooned. At the same time, increasing commodity prices, wage pressures, and loose monetary policies unleashed inflation. Large segments of the domestic economy were deregulated. Despite efforts in the 1980s to create trade, financial, and exchange rate stability, both the domestic and international economy were marked by crises — Third World debt, U.S. budget and balance of payments deficits, higher interest rates, and the collapse of the domestic savings and loan industry. While the American economy grew (erratically), the system could have come off the rails, and in many ways, the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe masked some of the deep problems within the post-Bretton Woods system.

The third period, which began in the early 1990s and lasted through the 2008 global financial crisis, might be thought of as the period of unfettered globalization or the so-called Washington consensus, which emphasized fiscal responsibility, monetary stability, privatization, and the increased global movement of goods, capital, and ideas. The United States managed to get its own domestic house in order, driving down its budget deficits, lowering its interest rates, and benefiting from the productivity gains emerging from the nascent technology revolution in Silicon Valley. The World Trade Organization was created in 1995 and China was welcomed as a member in 2001, massively increasing global trade. The system did have crises in Mexico in 1994 and Russia and East Asia in 1998, but global growth, especially in East Asia, was impressive.

The fourth period was the 2008 crisis and its aftermath, and we are still trying to make sense of it. On the one hand, innovative policies, both by the Obama administration and Ben Bernanke’s Federal Reserve, likely prevented a deep recession from developing into a global depression. On the other hand, the economic recovery was slow and often inequitable, and a dissatisfaction with the politics of both the crisis and recovery helped drive populist nationalism, both in the United States and abroad. Arguably, no real economic “system” emerged from the crisis, either at home or internationally, offering the Biden administration an opportunity in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic to rewrite and rebuild the rules of both the domestic and international economy, while creating a more durable, prosperous, and equitable system.

The Way Forward?

If the Biden administration is to place domestic and foreign economic policy at the heart of its national security strategy, there are at least five big questions about the future of the American economy and how it relates to U.S. national security strategy that must be examined.

First, how will the United States respond to the ongoing transformation of the domestic and international economy? Economic success going forward will be less based on traditional measures and low value-added activities, such as agriculture, resource extraction, low-end services, and even mass industrial prowess. Growth will increasingly emerge from generating and implementing technological innovations, as well as from the ability to creatively finance them. New technological breakthroughs in AI and machine learning, quantum computing, automation and robotics, 3D printing and advanced manufacturing, biomedicine, nanotechnology, etc. have the potential to revolutionize fields ranging from energy and health to manufacturing and transportation. Will the United States generate and adapt to these innovations, while also providing its population with the skills necessary to thrive in this new world? Success in the technology and financial realm have also tended to increase inequality, while also worsening geographical divisions between innovation hubs (Boston, San Francisco, New York, Austin) and other parts of the country. Will the government devise wise policies to ameliorate these frictions without losing the benefits of innovation?

How this question is answered is largely a matter of domestic politics. Yet how it is answered will shape both America’s global competitiveness and its political and societal well-being.

Relatedly, will the United States reject globalization and turn inward? In many communities, intense globalization is associated with de-industrialization and offshoring, despair and the opioid crisis, debt and inequality, climate change, and the rise of China. The United States has, throughout its history, gone through periods where it has turned its gaze away from the international economy. These historical episodes have rarely ended happily. Is there a way to capture the benefits of globalization while minimizing the harmful excesses?

The third question concerns the future of America’s economic relationship to China. The argument for decoupling and reducing vulnerability to China is powerful. First, COVID-19 demonstrated the dangers of vulnerable supply chains. Second, it does not make sense to continue to enrich a current and future rival. Third, increasing automation and robotics means that labor cost differentials are a less compelling reason to offshore production. For those who are skeptical of the pacifying effects of interdependence and believe security concerns should always trump economic ones, pulling away from China’s economy is the obvious choice.

The problem is that left to its own devices, the American and Chinese economies won’t naturally decouple. General Motors sells more cars, and Apple has sold more iPhones, in China than in the United States. Supply chains remain deeply integrated, including on the high-end technology front. Dissolving those relationships will be costly. Trade today is less between countries than within firms, whose operations are global rather than national. Shared technology platforms increase productivity, which would be lost under decoupling.

Trade flows, however, do not begin to capture the deep integration between the two economies. The financial and monetary spheres are far more interconnected. Chinese companies are raising record amounts on Wall Street, while U.S. banks and financial firms increase their investment and business in China. Despite political strains over the past decade, direct investment and financing in both directions shows little signs of decreasing. Reversing economic interdependence — if that policy is chosen for national security purposes — will both be costly and require political will. It would also fully signal that the United States sees China not as a competitor or even a rival, but as a full-blown adversary.

What are the sources of innovation and adaptation, and what role will the national government play in facilitating creating, scaling up, and implementing new technologies? This is the fourth big question faced by the Biden administration, and the issue here will be shaped by its view of U.S. competition and antitrust policy. On the one hand, the recent computing and telecommunications revolution has revealed the power of companies that dominate networks and platforms. The United States has done very well in this new world, and there are important arguments that the government should applaud and support the success of American tech giants dominating the global economy. On the other hand, some experts question whether it is healthy from a competition, innovation, and fairness perspective to allow companies like Amazon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft to achieve such dominating market power. They harken back to the spirit of President Theodore Roosevelt and his controversial but popular program of trust-busting in the early 20th century. There are critical national security considerations to both views.

Relatedly, there is a long-debated question of the role the government should play in seeding, supporting, subsidizing, and even directing the private sector. The United States has long steered clear of national economic planning. Yet the Chinese government’s massive, directed investments and championing of its companies, both for economic and national security reasons, has caused many Americans to rethink their priors on the relationship between the state and the private sector. This is reflected in the impressive, bipartisan support for the Endless Frontier Act to support improved technological competitiveness vis-à-vis China.

The final question involves America’s role as the banker to the world. Will the United States continue in this role, and what will the consequences be? This question has two parts, the first involving international monetary policy, the second surrounding capital formation.

One of the most important global economic developments of the past 15 years has been the emergence of the Federal Reserve Bank as the lender of last resort, not just to the United States, but to the world. The Federal Reserve banking system demonstrated masterful adaptability and far-sighted innovation during both the 2008 financial crisis and the economic fallout from last year’s COVID-19 crisis that, in both cases, arguably prevented a global depression and increased its mandate well beyond securing the U.S. financial system. In the process, it quietly but significantly increased America’s already potent global monetary and financial power. Despite previous predictions to the contrary, it is and will remain for some time a dollar-dominated world. Will this increased monetary power marry up with America’s recent proclivity to deploy economic sanctions, and if so, will that add or diminish American economic influence over the long term?

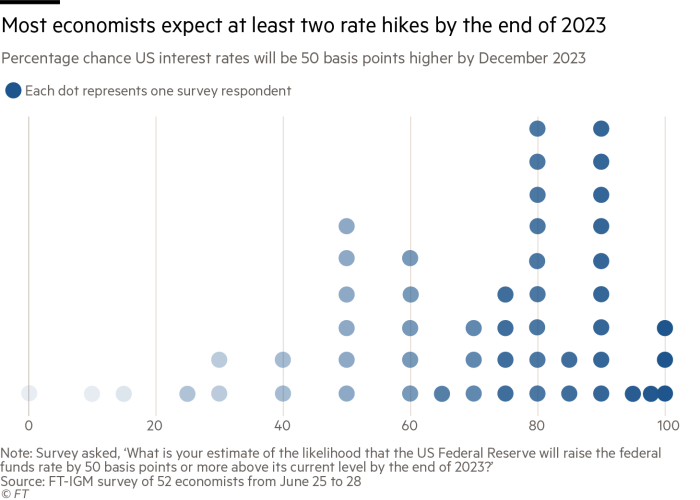

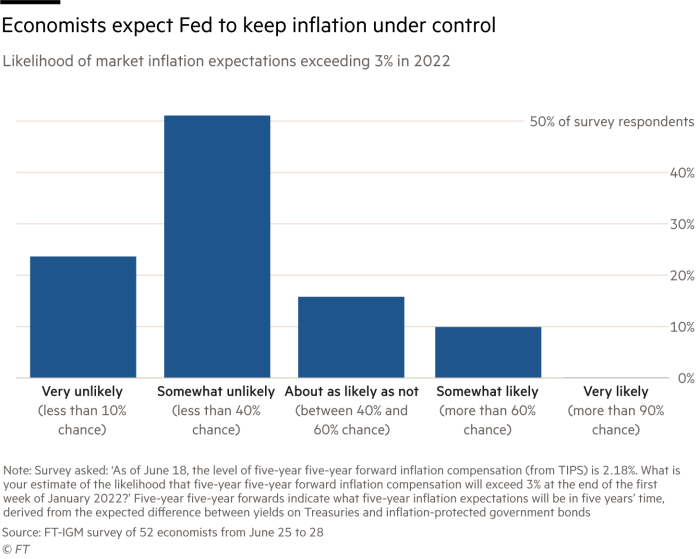

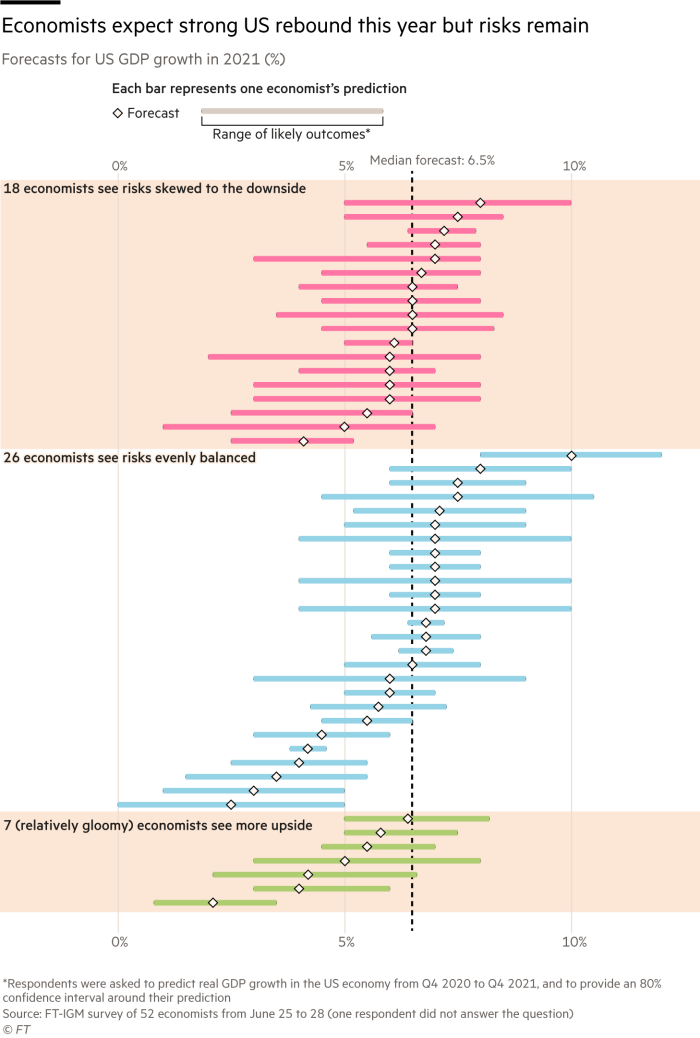

Part of the answer will be shaped by the uncertain outcome of current economic policies. The United States is currently undergoing a consequential experiment, with relative loose fiscal and monetary policy leading to a rethinking of how much debt and liquidity the economy can contain. Will this produce destabilizing inflation and a return to 1970s stagflation? Or will this liquidity be efficiently absorbed into higher productivity, a reduction in inequality, and overall growth? Interest rates, both nationally and around the world, remain near historical lows, despite the surge in liquidity.

The second aspect to America’s global financial power comes in its world leading innovation, sophistication, and depth of its financial sector. In recent decades, New York City competed with Hong Kong and London as the best place to raise capital and list companies. As recently as a decade ago, New York’s competitors showed signs of taking the lead. Great Britain’s decision to leave the European Union and China’s decision to crack down on dissent in Hong Kong has moved the advantages back to the United States. In addition to the traditional methods of Wall Street finance and exchange listings, America’s innovative venture capital financing capabilities in Silicon Valley, Boston, Austin, and elsewhere provide important and impressive domestic and global advantages. Can they be maintained and expanded upon?

Conclusion

Will the Biden administration’s efforts to link economic and national security succeed? While a commendable goal, accomplishing it may not be as easy or simple as one might think. To do so, U.S. officials would be wise to recognize the complex, often contradictory factors shaping economic and security goals, calculating how best to resolve the tension while advancing both. Foreign economic policy is about a lot more than trade policy, for example, and the most effective long-term policy toward China likely eludes simple binaries. They should also keep in mind America’s unique history and perspective on the purpose of economic statecraft, which is often at odds with other countries. Finally, the administration should recognize and generate policies to deal with the profound economic changes wrought by the larger technological and financial transformation of both the national and global economies. The United States is at an inflection point, both in how its economy operates and in the global security landscape it faces. How it handles the balance between the two — generating wealth while also creating security — will have consequences for years to come.

Francis J. Gavinis the Giovanni Agnelli Distinguished Professor and the inaugural director of the Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He is also the Chairman of the Board of Editors of the Texas National Security Review. Gavin has written several books, including Gold, Dollars, and Power: The Politics of International Monetary Relations, 1958-1971.

Image: U.S. Air Force (Photo by Staff Sgt. Christopher S. Muncy)

Adblock test (Why?)

Economics and US National Security - War on the Rocks

Read More